Coastal Systems and Landscapes

Sources of energy in coastal environments

1. Wind: The primary driver of coastal energy

Almost all wave energy originates from the Sun, which heats the Earth unevenly, generating pressure differences in the atmosphere. These pressure differences generate wind, which transfers energy to the sea surface, thereby generating waves.

What determines wind-generated energy?

Wind strength

Stronger winds transfer more kinetic energy to the water surface, producing larger and more powerful waves.

Duration

The longer the wind blows, the more fully waves can develop.

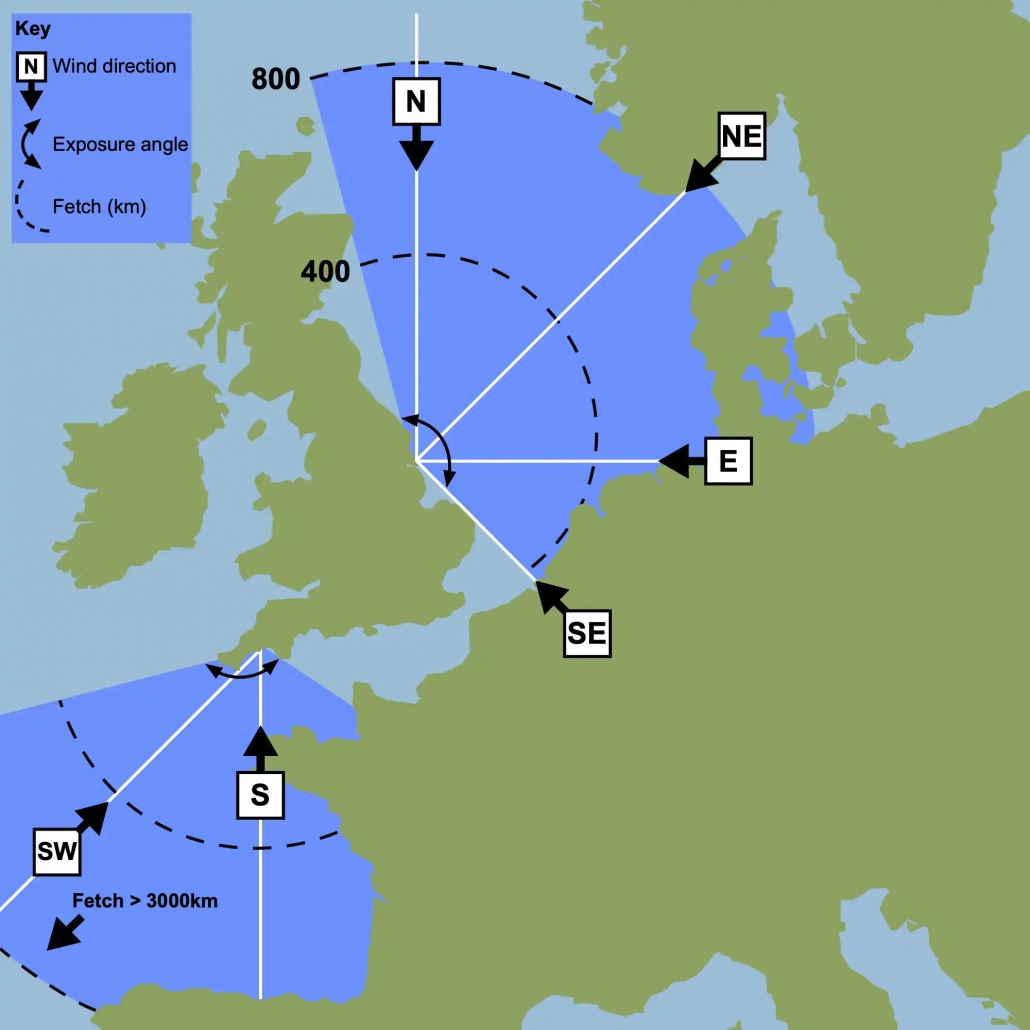

Fetch

The uninterrupted distance over which the wind blows. Long fetches, such as across the North Atlantic, produce highly energetic wave conditions.

Together, these factors explain why some coastlines experience dramatic wave energy while others remain relatively calm.

Wind also initiates aeolian processes, moving dry sand inland and contributing to the formation of dune systems.

2. How do waves form?

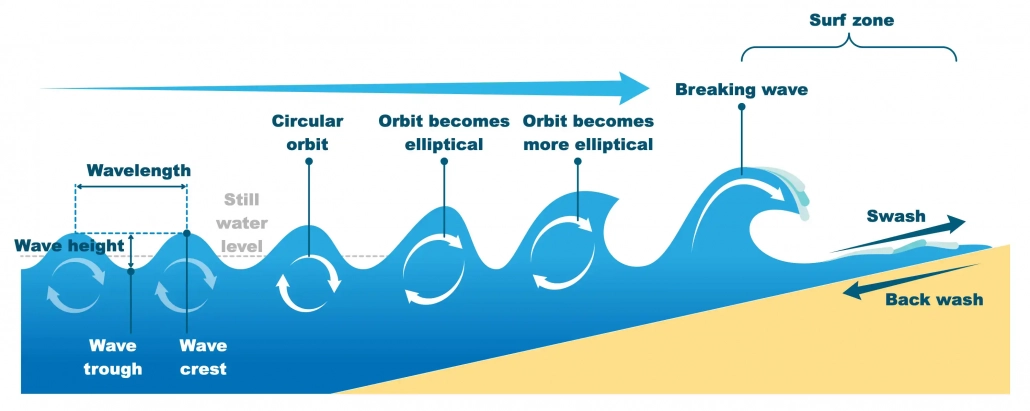

Waves result from the orbital motion of water particles as wind energy is transferred to the sea. As waves approach shallow water, their behaviour changes:

- The circular motion of water becomes increasingly elliptical.

- Wave height increases and wavelength decreases.

- Once the wave becomes too steep, the crest collapses, and the wave breaks as swash rushes up the beach and backwash drains back down.

This transformation is critical because it determines how much energy reaches the coast and whether erosion or deposition is more likely.

3. Constructive and destructive waves

Different wave types lead to contrasting coastal responses.

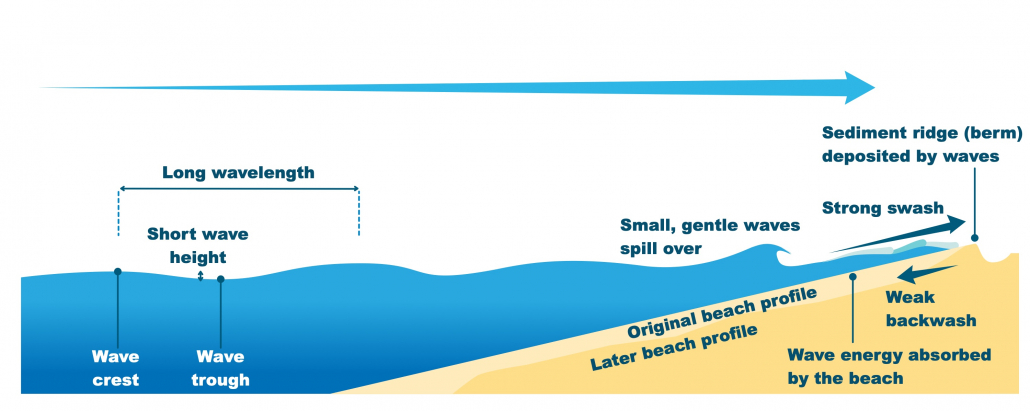

Constructive Waves

- Low height, long wavelength

- Strong swash carries sediment landward

- Weak backwash encourages deposition

- Build gently sloping beaches

- Typical of calmer weather conditions

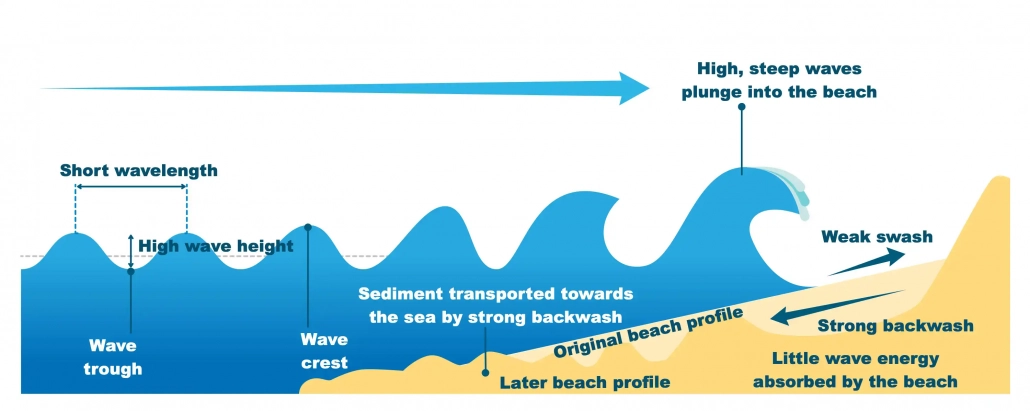

Destructive Waves

- High height, short wavelength

- Weak swash but very strong backwash

- Remove sediment from beaches

- Create steeper profiles

- Common in stormy or high-energy conditions

Constructive waves tend to widen beaches, whereas destructive waves erode them, often creating a negative feedback loop as beach profile adjustments modify the waves’ impact over time.

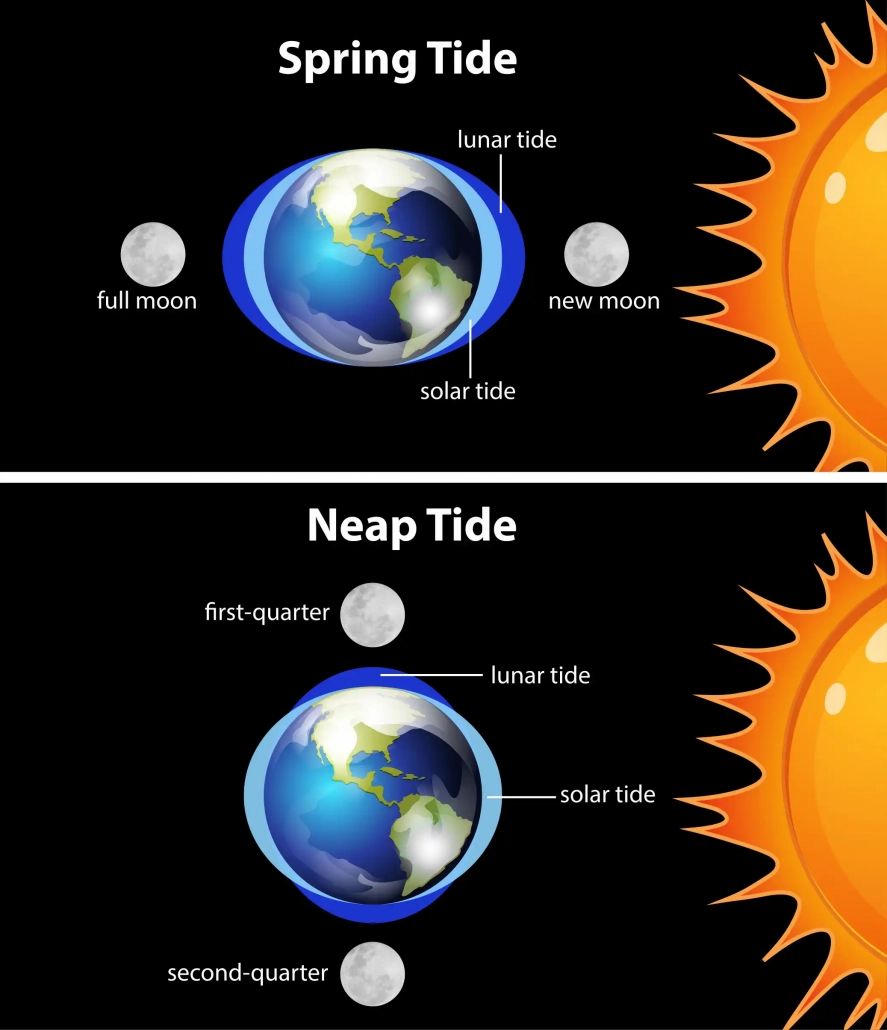

4. How do tides influence coastal energy?

Tides are produced by the gravitational interactions among the Moon, Earth, and the Sun, creating rhythmic rises and falls in sea level.

Tidal range matters because it influences:

- The vertical zone affected by marine processes

- The concentration of erosion, particularly around high tide on cliffed coasts

- The strength of tidal currents, especially in estuaries and narrow channels, where water movement can accelerate dramatically

High tidal ranges expose large areas to erosion and deposition, while low ranges restrict processes to a narrow strip of coastline.

5. Currents: Moving water and sediment

Currents also transfer energy within the coastal system.

Longshore currents

When waves approach at an angle, they generate longshore drift, transporting sediment parallel to the coastline and shaping features such as spits and barrier beaches.

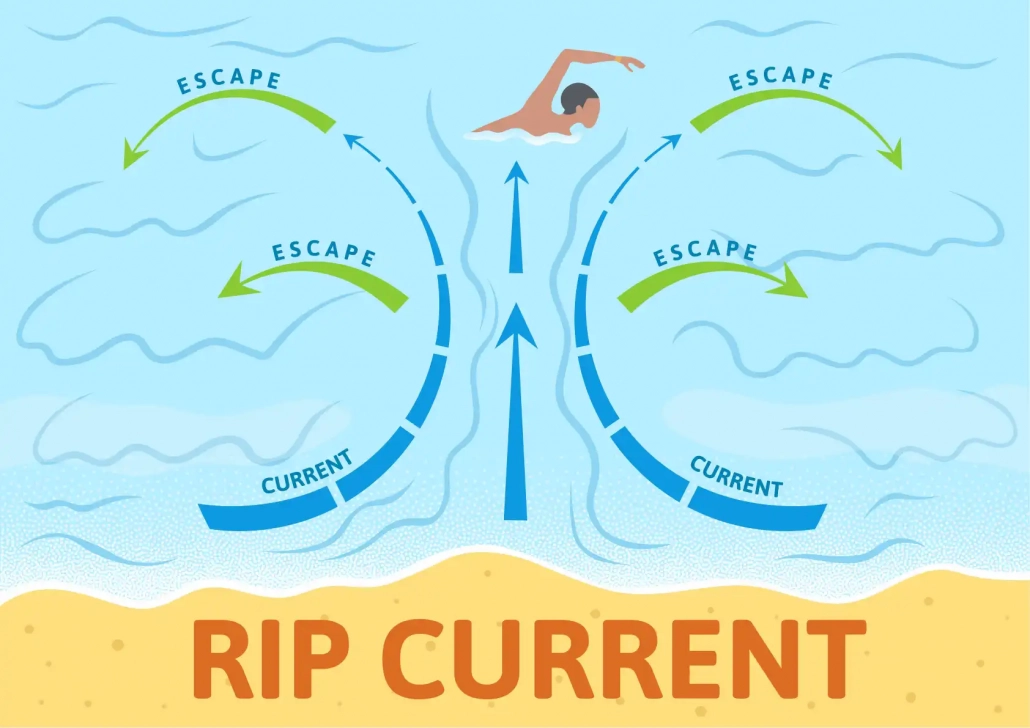

Rip currents

Narrow, fast-moving flows of water move seaward. They often form when breaking waves push water up the beach, which then funnels back offshore in confined channels. Rip currents intensify localised erosion by redirecting energy away from the shore in a focused stream.

Tidal currents

Created by the rise and fall of tides, these can be especially powerful in constricted environments, influencing sediment transport, channel formation and estuarine morphology.

High-energy and Low-energy Coasts

Different coastlines experience varying levels of wave and tidal energy, resulting in distinctive landscapes.

High-energy Coasts

Strong prevailing winds, long fetches and frequent storm conditions shape these coastlines.

Characteristics

- Dominated by destructive waves

- High rates of erosion

- Exposed rocky shorelines with steep profiles

- Landforms such as cliffs, caves, arches, stacks and wave-cut platforms

- Sediment budgets where removal often exceeds deposition

Coasts facing major oceans—such as western Britain—clearly illustrate this high-energy regime.

Low-energy Coasts

These coastlines develop where waves lose energy due to shelter, short fetches or shallow offshore profiles.

Characteristics

- Dominated by constructive waves

- Deposition outweighs erosion

- Wide sandy beaches, spits, salt marshes and mudflats

- Gentle beach gradients

- Often found in estuaries, bays or behind offshore barriers

Such environments create extensive sediment stores and depositional landforms.

6. Wave refraction: Why energy is not spread evenly

As waves approach irregular coastlines, they bend due to changes in water depth. This process, wave refraction, redistributes energy:

- Energy is focused on headlands, increasing erosion

- Energy is dispersed in bays, encouraging deposition and beach formation

This explains why erosional features develop on projecting sections of coast while depositional features accumulate in more sheltered areas. Refraction also forms part of a broader feedback system that reinforces the headland–bay pattern through time.

Why energy is fundamental to coastal landscapes

The combination of wind, waves, tides and currents shapes every coastal environment:

- Determines where erosion or deposition occurs

- Influences sediment budgets

- Controls beach profiles and shoreline stability

- Governs the formation and evolution of landforms

- Creates contrasting coastal landscapes based on the energy regime

Understanding these energy sources allows geographers to explain why coastlines differ and how they may respond to environmental change.

Exam Tip

Always Anchor Your Explanation in the System

When answering questions on coastal systems, don’t just describe processes (e.g., erosion, transportation, deposition). Examiners reward answers that explicitly link these processes to system concepts such as inputs, outputs, stores, transfers, feedback and dynamic equilibrium.

How to show this in an exam answer

- Use system language: “This increases the sediment input…”, “This transfer of material…”, “The store of beach sediment…”

- Explain consequences: show how a change in one part of the system affects another.

- Identify feedback: e.g., “This leads to negative feedback because…”

- Refer to equilibrium: show whether the coastline is moving towards or away from balance.

Example of a high-level phrase

“A reduction in sediment supply disrupts dynamic equilibrium, narrowing the beach store. This increases wave energy at the cliff foot, triggering a positive feedback loop that accelerates erosion.”

Using this kind of phrasing demonstrates conceptual understanding — exactly what AQA expects for the higher marks.